Models of Practice

Research summary

Supporting diverse learners, including students on the autism spectrum, is a major task facing teachers today.

The challenges that diverse learners experience can make accessing the curriculum harder for them. Teachers need to be aware of students’ unique learning, and use research-supported practices to provide appropriate accommodations and adjustments for all students.

The two Models of Practice in this research project enable teachers to make informed choices about the classroom environment, communication style, and learning activities they choose for students on the spectrum.

Teachers in the project’s trial reported that these Models of Practice provide useful strategies that were:

- well organised

- easy to read

- useful for students with a range of needs.

Research aim

The aim of the project was to develop, trial, and evaluate Models of Practice that contain:

- accessible and relevant resources

- professional development material.

These Models of Practice were designed for mainstream teachers of students on the autism spectrum in Australian schools.

The two Models of Practice are for teachers of:

- early years (EY): Prep/kindergarten and into Year 1

- middle years (MY): Year 7 and into Year 8.

Project objectives and outcomes

Read more about the project's objectives and outcomes.

Key elements

A Model of Practice is an organisational framework made up of evidence-informed practices. Each practice is accompanied by a brief that helps teachers to implement the practice in their classrooms.

The two Models of Practice on inclusionED support teachers to make decisions about their everyday classroom practice with students on the autism spectrum.

The Models of Practice that were designed and trialled in this research project are listed below. You can also download this information in the quick reference guides below.

Practices

Belonging |

Being |

Becoming |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Practices

Rigour |

Relevance |

Relationships |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Organisers

The Model of Practice uses the organisers:

- Rigour: Evidence-informed instruction and support

- Relevance: Engaging instruction that builds on students’ strengths and skills to achieve post-schools goals

- Relationships: Incorporating special interests in schoolwork; social-emotional capabilities.

Practices under these three organisers must meet the following criteria:

Rigour

- appropriate accommodations

- individualised support

- challenging learning opportunities

Relevance

- career development

- self-determination

- recreation/leisure

Relationships

- social interaction

- strengthening supportive relationships

- social challenges

- emotional support.

Quick reference guide

Model of Practice – Early years: Quick reference guide

Model of Practice – Middle years: Quick reference guide

Our evidence base

What is design-based research?

Design-based research (DBR):

- addresses research problems in education that are ‘both scientifically and practically significant’ (McKenney & Reeves, 2013)

- produces research outcomes that affect practice.

DBR uses an iterative, cyclical process consisting of:

- design

- evaluation

- redesign

- mixed-methods data collection.

In DBR, researchers collaborate with practitioners in real-world educational contexts.

The design of the two Models of Practice, including each practice brief, was informed by the design principles of Falconer, Finlay, and Fincher (2011).

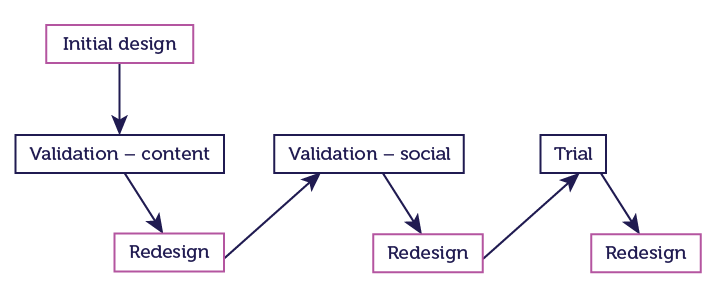

The DBR process in the Models of Practice project

The Models of Practice (MoP) were developed using the design–evaluate–redesign method described above, in the following steps:

- Design: The initial ideas for the practices were developed into Prototype 1.

- Evaluation: The content in Prototype 1 was validated. The practices were refined and redesigned according to the findings of this content validation process. The result was called Prototype 2.

- Redesign: The social validity of the Prototype 2 practices was tested. The Prototype 2 practices were refined and redesigned according to the findings of the social validation process, and became Prototype 3.

- Mixed-methods data collection: Prototype 3 was trialled in classrooms, with the early years (EY) comprising 29 practices and the middle years (MY) comprising 36 practices.

This process is explained in more detail below for each Model of Practice.

The graph shows the stages of the process.

The process for developing the Models of Practice.

The table below shows how the practices were refined as they went through the process.

Stage 1: Design–evaluate–redesign process

The team aimed to answer the following research question:

Which practices should be embedded in the Model of Practice to support teacher decision-making in relation to the effective education of students on the autism spectrum as they move between early and middle years classrooms?

To answer this research question, the team used the following steps:

Design

- Initial design completed by researchers. The team identified:

- relevant, comprehensive, teacher-based practices with evidence to support them, including two potential lists for young children with disabilities1

- five practice-based publications2

- The design was scrutinised for alignment with the organisers of Belonging, Being, and Becoming.

- 163 practices were scrutinised by the team.

- 31 potential practices were progressed.

Evaluate: Content validity

- 31 practices were evaluated by five experts in the autism spectrum and education.

- The context validation index was calculated, and practices were retained only if their content validity was excellent according to the index.

- 31 practices were progressed.

- Practices were refined and redesigned. One practice was separated into two.

- 32 practices were progressed.

Evaluate: Social validity

- 32 practices were evaluated via an online survey completed by 129 Australian teachers. Teachers were asked if they considered each practice to be informed by evidence, and if they used the practices in their classrooms.

- 32 practices were retained.

Redesign

- Practices were refined and redesigned considering feedback.

- Practice briefs were developed.

1. Division for Early Childhood Recommended Practices [DEC], 2014; Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning, 2013.

2. Hurth, E., Izeman, Whaley, & Rogers, 1999; Iovannone, Dunlap, Huber, & Kincaid, 2003; Long & Simpson, 2017; Simpson & Crutchfield, 2013.

The early years practices that were trialled are listed in ‘Key elements’ above.

Read more about each practice on the relevant practice page of inclusionED.

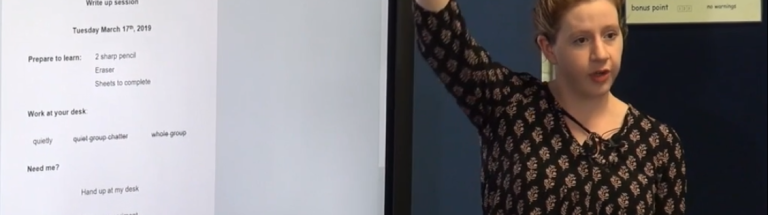

Stage 2: Trialling the Model of Practice with Australian teachers

Trial design

Before the trial, the team wanted to find out what teachers thought of the Model of Practice. The team:

- surveyed teachers. Teachers rated their knowledge and confidence. The survey included some items from the published rating scale called the Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy Scale (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001)

- interviewed 33 teachers. Teachers commented on their knowledge and confidence with the specific student group.

During the trial, the team wanted to find out about the level of support teachers received. To find out which methods of support work best, the team offered teachers:

- face-to-face coaching

- online coaching

- access to online resources and practice briefs only.

After the trial, the team wanted to find out about teachers’ experiences using the Model of Practice. The team:

- surveyed 33 teachers

- interviewed 27 teachers.

At the end of the trial:

- 15 teachers were 'active users' of the practices

- 4 teachers were 'superficial users'

- 8 teachers were 'non-users'.

Participants

38 teachers from 23 schools in New South Wales, Queensland, and Victoria took part in the trial.

Information about schools and teachers that participated in the trial is shown in the table and graphs below.

Findings

Initial impressions of the early years Model of Practice

Teachers' initial impressions of the early years (EY) Model of Practice and the practices associated with each of the three organisers – Belonging, Being, and Becoming – are summarised below.

Familiarity with practices

The Model of Practice and/or practices were familiar to teachers and made sense to them. Some teachers recognised the model (and the organisers of Belonging, Being, and Becoming) because they know the Early Years Learning Framework (DEEWR, 2009).

‘I love that it's aligned with the Early Years Learning Framework.’

Other teachers recognised that the EY Model of Practice was a new practice framework but the practices themselves were familiar.

‘It’s quite familiar, all the descriptions, but I’ve never seen it laid out like that, under Belonging, Being, and Becoming.’

‘It was all quite familiar, I thought – yeah, that makes common sense; yep, you need to do that; yep.’

Important and useful

Teachers noted the importance or usefulness of the individual practices to early years education.

‘I really think that the class rules and those class schedules and everything are just so important.’

‘I just think the social-emotional learning is very important to me and my kids.’

‘I agree with all the practices that are mentioned there. I think they’re all … equally as important as each other.’

Some teachers thought the practices in the Becoming organiser were secondary to those in Being and Belonging.

‘In order for them to be calm, I think they need to have to be able to have that feeling of Being and Belonging, so I do feel like that’s third in line to the other things, because … I think the Becoming part has to come as a result of the other things being in place.’

About one third of the teachers considered the practices useful for all students.

‘I thought it sort of comprises everything we want for not just … ASD students, but also for any student in a class.’

Teachers’ experiences of using the EY Model of Practice

27 teachers were interviewed about using the Model of Practice.

Facilitators supporting teachers

Teachers thought the EY Model of Practice was a valuable resource.

‘It’s benefited the children, it’s benefited me, and I’ve got a great resource that’s here, that’s self-explanatory, easy to read.’

EY practices were beneficial for all students.

‘Those routines help all Preps, especially … my boy with autism … but it benefited the whole class.'

Teachers thought that foundational practices made the Model of Practice particularly suitable for early-career teachers, recent graduates, or pre-service teachers.

‘I hope all new teachers can get their hands on it.’

‘I actually showed my student teacher, and she found it really helpful.’

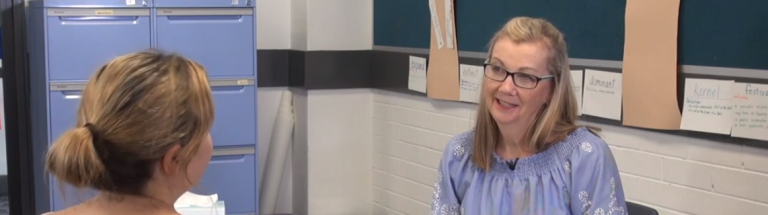

Teachers placed high value on the professional support they received from coaches.

A close association was observed between active use of the EY Model of Practice and the professional support teachers received: All teachers who received face-to-face support implemented parts of the model in their classrooms.

Barriers to teachers' use of the EY Model of Practice

The main barrier to teachers using the Model of Practice was lack of time or lack of support.

‘It wasn't the fact that I actually thought about not going back to it … It was just time constraints – with so much stuff happening with work.’

‘I think it was a bit of the time restraints, and trying to get everything done also with our everyday teaching and commitments, and assessments, and reporting – just everything of the everyday teaching world, I think, made it quite difficult.’

‘I think the model itself is fantastic, but it would be good to have someone come out and explain it to us – actually someone coming out and explaining it to us is much better than us reading it and trying to implement it ourselves.’

Practices adopted by teachers

The following practices were adopted most often by teachers:

Teacher knowledge, confidence, and capability

The ratings given by teachers to the Model of Practice revealed significant changes in teachers’ perceptions of their knowledge, confidence, and capability related to teaching students on the autism spectrum in the early years.

Before teachers used the EY Model of Practice

Before they used the Model of Practice, around two thirds of teachers rated their knowledge and confidence between moderate to high.

‘I probably would have just put average, I’d say – I don’t feel panicked about it, but I know that there’s still a lot to learn about it, for me.’

‘Some days I feel like, yup, I’ve made a positive impact, and other days I’m like “Oh my God,” … “What have I done?” I guess it's up and down all the time.’

After trialling the EY Model of Practice

Active users of the Model of Practice reported increased knowledge, skills, or feelings of capability.

‘Just by accessing the model and the practice briefs has maintained what I already knew, but it's also deepened my knowledge. And the hyperlinks to outside sources extends that even further.’

‘I think because being able to identify why things weren't working has really helped. So, it's certainly improved my confidence, but also not being so hard on myself with a few things as well.’

Did coaching make a difference to teacher uptake?

Teachers who received professional support from coaches to select and implement practices were more likely to adopt the model.

- All 9 teachers who received face-to-face support in the trial implemented the practices.

- 3 of the 4 teachers who received support over the phone implemented the practices.

‘We just unpacked the briefs a lot more. I think we were … quite lost before we had the coach – it was very valuable having her coming out. I think we were just trying to focus on too many briefs at once.’

‘I think the model itself is fantastic, but it would be good to have someone come out and explain it to us.’

Stage 1: Design–evaluate–redesign process

The team aimed to answer the following research question:

Which practices should be embedded in the Model of Practice to support teacher decision-making in relation to the effective education of students on the autism spectrum as they move between early and middle years classrooms?

To answer this research question, the team used the following steps:

Design

- Initial design completed by researchers. The team identified potential teacher practices. Practices included in the design stage had to meet five conditions:

- evidence-based (see definition below)

- suitable for general education classroom teachers (rather than learning support teachers)

- whole-class strategies

- mainstream school–focused

- single-step program.

- The design was scrutinised for alignment with the organisers of Rigour, Relevance and Relationships.

- 135 practices were scrutinised by the team.

- 44 potential practices were progressed.

How is 'evidence-based' defined?

… a practice is considered evidence based if it was supported by:

(a) two high quality experimental or quasi-experimental design studies conducted by two different research groups, or

(b) five high quality single case design studies conducted by three different research groups and involving a total of 20 participants across studies, or

(c) a combination of research designs that must include at least one high quality experimental/quasiexperimental design, three high quality single case designs, and be conducted by more than one researcher or research group.

Wong, Odom, Hume...Schultz (2015) p.1958

Evaluate: Content validity

- 44 practices were evaluated by five experts in the autism spectrum and education.

- The context validation index was calculated, and practices were retained only if their content validity was excellent according to the index.

- 6 practices were progressed.

- Practices were refined and redesigned.

- 38 practices were progressed.

Evaluate: Social validity

- 38 practices were evaluated via an online survey completed by 129 Australian teachers. Teachers were asked if they considered each practice to be informed by evidence, and if they used the practices in their classrooms.

- 36 practices were retained.

Redesign

- Practices were refined and redesigned considering feedback.

- Practice briefs were developed.

The middle years practices that were trialled are listed in ‘Key elements’ above.

Read more about each practice on the relevant practice page of inclusionED.

Stage 2: Trialling the Model of Practice with Australian teachers

Trial design

Before the trial, the team wanted to find out what teachers thought of the Model of Practice. The team:

- surveyed 31 teachers. Teachers rated their knowledge and confidence. The survey included some items from the published rating scale called the Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy Scale (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001)

- interviewed 33 teachers. Teachers commented on their knowledge and confidence with the specific student group.

During the trial, the team wanted to find out about the level of support teachers received. To find out which methods of support work best, the team offered teachers:

- face-to-face coaching

- online coaching

- access to online resources and practice briefs only.

After the trial, the team wanted to find out about teachers’ experiences using the Model of Practice. The team:

- surveyed 15 teachers

- interviewed 27 teachers.

Participants

34 teachers from nine schools in New South Wales, Queensland, and Victoria took part in the trial.

The middle years (MY) Model of Practice trial took place over an eight-week period in Terms 3 and 4.

Scheduling for each teacher to receive coaching was problematic in MY. One member of staff from each participating school was nominated as an Autism Instructional Leader (AIL). The AIL received coaching support, and then supported other teachers at their school.

Information about schools and teachers that participated in the trial is shown in the table and graphs below.

Findings

Initial impressions of the middle years Model of Practice

Teachers' initial impressions of the MY Model of Practice and the practices associated with each of the three organisers – Rigour, Relevance, and Relationships – are summarised below.

Familiarity with practices

The practices were familiar to most of the teachers interviewed. Several teachers reported that they already used some of the practices.

Even though the practices were familiar, reading through the MY Model of Practice prompted them to evaluate their use of the practices.

‘When I was reading over these things I said: I do that, I do that. I think I said that I need to do a few of those better.’

Good teaching practice

Teachers reported that the Model of Practice represents good teaching practice in general. They thought that the Model of Practice was:

- accessible

- user-friendly

- presented in a way that made sense to teachers.

‘I really liked it. I think that it just makes sense.’

The Relationships organiser was recognised as an area of importance that should be a focus in teachers’ development.

‘We also need to make sure that we have a good relationship not just with the students, but the family and even the community.’

Teachers’ experiences of using the EY Model of Practice

The 15 teachers surveyed included 6 AILs.

Teachers who used the practice briefs described them as useful and said they would share them with colleagues. Teachers identified three key enablers and barriers to their engagement with the Model of Practice.

Facilitators supporting teachers

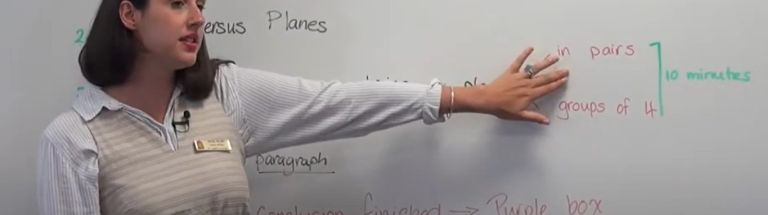

Teachers thought the MY Model of Practice offered good strategies, which were presented in well-laid-out, accessible briefs.

‘The three areas are well named with the three Rs – a good memory hook. When I discovered the practice briefs, they made a lot more sense to me. Colour coding was helpful. Spoken in everyday language. Addressed many facets of practice. Layout great – not overcrowded.’

Teachers valued the support provided by AILs and coaches.

‘Face-to-face dialogue is the most effective way to learn and be guided.’

The Model of Practice was considered to be a great reflective tool. While teachers were familiar with many of the practices, the Model of Practice served as a reminder to teachers to reflect on their practice, think about what they were doing well, and identify strategies to further their practices.

‘It allows the teacher to reflect on their own practices to ensure they cater for all students.’

Barriers to teachers' use of the EY Model of Practice

Teachers reported that a lack of time and support was the most significant challenge.

Most teachers had to use their own time (e.g. lunchtime) as no release time was available. One of the better supported teachers noted that the principal took their class.

The timing of support sessions was also important.

‘Information sessions were too spread out. I would constantly need to be reminded what it was and re-explained some things when we started it.’

Some teachers also reported a greater need for explicit instruction on how to use the Model of Practice.

‘Felt a little at sea with some things, especially in the beginning – an expert would have been helpful to give a big picture or summary of the practices and briefs and how they work together.’

Practices adopted by teachers

The following practices were adopted most often by teachers:

Teacher knowledge, confidence, and capability

The ratings given by teachers to the Model of Practice revealed significant changes in teachers’ perceptions of their knowledge and confidence related to teaching students on the autism spectrum in the middle years. Of the 15 teachers surveyed:

- nine reported an increase in their knowledge

- 12 reported an increase in their confidence.

Before teachers used the EY Model of Practice

Before they used the Model of Practice, teachers identified limited confidence due to:

- challenges with balancing the various needs in the class

- a lack of support

- limited experience with behaviour management

- limited experience with students with additional needs

- insufficient time to spend with students.

After trialling the EY Model of Practice

Teachers reported that their confidence increased due to:

- establishing relationships with students

- engaging with families and carers

- using structured classrooms

- collaborating with colleagues

- receiving support from the school.

- No teachers rated their knowledge or confidence as decreasing.

Did coaching make a difference to teacher uptake?

Only the AILs received professional support and were interviewed about this. AILs who received coaching reported complete satisfaction with:

- communication

- collaborative style

- effectiveness

- productivity

- capacity building.

Meet the researchers

Dr Wendi Beamish

Jane Cotter

Miss Emma Gallagher

Ms Vicki Gibbs

Dr Libby Macdonald

Ms Ainslie Robinson

Dr Annalise Taylor

Dr Trevor Clark

Dr Susan Bruck

All researcher details including names, honorifics (for example ‘Dr’), and organisational affiliations are correct at the time of the project.

Publications from this project

Articles informing this project

Anderson, T., & Shattuck, J. (2012). Design-based research a decade of progress in education research? Educational Researcher, 41(1), 16–25.

Beamish, W. (2008). Consensus about program quality: An Australian study in early childhood special education. Saarbrucken, Germany: VDM Publishers.

Beamish, W., Bryer, F., & Klieve, H. (2014). Transitioning children with autism to Australian schools: social validation of important teacher practices. International Journal of Special Education, 29(1), 1–13.

Cook, B. G., Cook, L., & Landrum, T. J. (2013). Moving research into practice: Can we make dissemination stick? Exceptional Children, 79, 163–180.

Elsabbagh, M., Yusuf, A., Prasanna, S., Shikako-Thomas, K., Ruff, C. A., & Fehlings, M. G. (2014). Community engagement and knowledge translation: Progress and challenge in autism research. Autism, 18, 771–781.

Goodyear, P. (2005). Educational design and networked learning: Patterns, pattern languages and design practice. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 21(1), 82–101.

Iovannone, R., Dunlap, G., Huber, H., & Kincaid, D. (2003). Effective educational practices for students with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 18, 150–165.

Hurth, J., Shaw, E., Izeman, S. G., Whaley, K., & Rogers, S. J. (1999). Areas of agreement about effective practices among programs serving young children with autism spectrum disorders. Infants and Young Children, 12, 17–26.

McKenney, S., & Reeves, T. C. (2012). Conducting educational design research. New York: Routledge.

Odom, S. L., McLean, M. E., Johnson, L. J., & Lamontagne, M. J. (1995). Recommended Practices in Early Childhood Special Education: Validation and Current Use. Journal of Early Intervention, 19(1), 1–17.

Peers, C. , & Fleer. M., (2014). The Theory of ‘Belonging’: Defining concepts used within Belonging, Being and Becoming—The Australian Early Years Learning Framework. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 46(8), 914–928.

Polit, D. F., Beck, C. T., & Owen, S. V. (2007). Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health, 30(4), 459–467.

Saggers, B., Klug, D., Harper-Hill, K., Ashburner, J., Costley, D., Clark, T., . . . Carrington, S. (2016). Australian autism educational needs analysis – What are the needs of schools, parents and students on the autism spectrum? Full report. Brisbane, Australia: Autism CRC.

Simpson, R. L., Mundschenk, N. A., & Heflin, L. J. (2011). Issues, policies, and recommendations for improving the education of learners with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 22, 3–17.

Test, D. W., Smith, L. E., & Carter, E. W. (2014). Equipping youth with autism spectrum disorders for adulthood: Promoting rigor, relevance, and relationships. Remedial and Special Education, 35(2), 80–90.

Wong, C., Odom, S., Hume, K. A., Cox, A. W., Fettig, A., Kucharczyk, S., . . . Schultz, T. R. (2015). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: A comprehensive review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(7), 1951–1966.

Practices

Provide a safe calm space for students

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- learn self-regulation

- reduce behavioural dysregulation

Harnessing student interests

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- be more engaged

- focus across topics

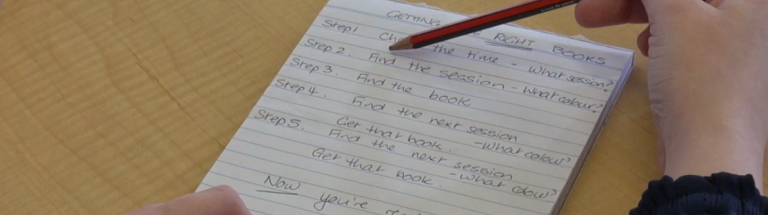

Use instructional sequences

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- transition smoothly

- know what to expect

Organise your classroom

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- access all classroom areas

- transition smoothly

Share information through home–school communication

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- be supported across settings

Establish classroom rules

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- know what is expected

- understand consequences

Respond constructively to student behaviour

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- build self-esteem

- stay on task

Use task analysis for skill development

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- learn new skills

- work independently

- build self-confidence

Strengthen school belonging and emotional trust

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- feel connected

- feel valued

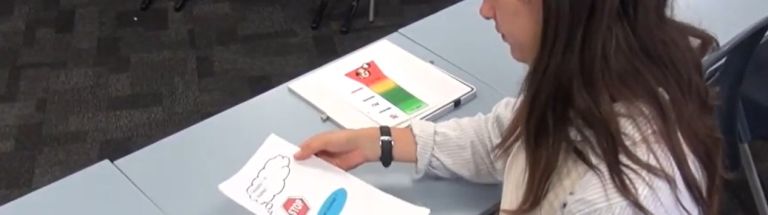

Use visual supports to increase understanding

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- learn new concepts

- follow lengthy instructions

Use visual self-management tools

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- build greater independence

- maintain on-task behaviour

Embedding opportunities for choice making

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- make decisions

- build independence

Develop exam preparation skills

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- improve confidence

- improve test performance

- decrease exam anxiety

Interact with every student

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- feel valued

- engage in interactions

Conduct an ABC analysis

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- be accepted by their peers

- feel supported

Adjust oral assessments for student success

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- reduce anxiety

- demonstrate knowledge

Create assignment exemplars

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- understand the task

- build confidence

Meet students' sensory needs

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- engage in tasks

- self-regulate

Harnessing student interests (Secondary)

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- be more engaged

- focus across topics

Establish classroom expectations (Secondary)

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- know what is expected

- understand consequences

Meet students' sensory needs (Secondary)

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- engage in tasks

- self-regulate

Organise your classroom (Secondary)

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- access all classroom areas

- transition smoothly

Strengthen school belonging and emotional trust (Secondary)

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- feel connected

- feel valued

Provide a safe calm space for students (Secondary)

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- learn self-regulation

- reduce behavioural dysregulation

Respond constructively to student behaviour (Secondary)

TEACHING PRACTICE

For student years

Helps students to

- build self-esteem

- stay on task